As a budding young journalist, I am slowly coming to terms with how many ethical and moral codes in which I will have to one day abide by – including honesty, independence, balance, fairness and accuracy. These codes are particularly important when covering stories that report on scientific facts, figures and findings where debate surrounding the issue are somewhat controversial. Bud Ward (2009) accurately states that one of the most important codes that a journalist must adhere to is to, “seek truth and report it” (p.13).

Ward relates much of his writings to the ways in which journalists are constrained to their paymasters’ interests and beliefs when it comes to topics such as climate change. Whilst some believe that there is no such thing and that it all simply a made-up, entirely false concept – we are not talking about Santa here, we are discussing a potentially devastating issue that can be prevented. The Sydney Morning Herald recently plastered pictures of the famous Bondi beach in 87 years if we continue with our wasteful, thoughtless ways.

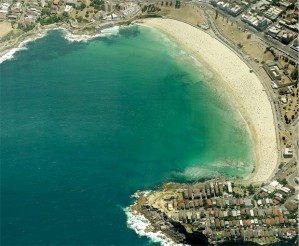

Bondi Beach today;

Bondi in 2100;

The Sydney Morning Herald is similar to that of the UK Telegraph who neither agrees nor denies that climate change is a prominent issue within today’s society. However, media such as Al Jazeera and the New York Times constantly present – and are adamant – that climate change is a scientifically proven issue.

This is another value that Ward (2009) highlights as integral to fair reporting, is the notion of ‘false balance’ within the media – especially when reporting on climate change as it is a highly debated and discussed issue in popular media today and it challenges many of the “strictest codes” (War 2009, p.13) in which a journalists must abide by.

But what constitutes as false balance? Is it Al Jazeera’s views because they resolutely state that climate change is real? And is this really a negative thing “or does it not matter, so long as the reporting is judged to be fair and independent?” (Ward 2009, p.14). I agree with Ward when he says, “instead of…providing ‘balance’ in reporting on news involving differing perspectives journalists increasingly, and rightly, take their clues from the leading and acknowledged scientific experts…” (Ward 2009, p.14).

It is unbelievably important that journalists present equal, honest and fair news for their audience whether it is reporting on a controversial issue or a simple, everyday news piece. But does balance really have to be an integral element when it comes to the truth?

I do not think so, especially if it is regarding something that is so easily altered if we know the cold, hard and sometimes unpleasant facts.

Sources: Ward, B 2009, Journalism Ethics and Climate Change reporting in a Period of Intense Media Uncertainty, in Ethics of Science Journalism, volume 9, pp. 13-15.

Hollywood has been internationally regarded as the media producing capital that trumps all others for nearly a century. But it seems that Hollywood’s days are numbered as other media capitals such as Bombay, Cairo and Hong Kong are set to dominate in this new era.

Hollywood has been internationally regarded as the media producing capital that trumps all others for nearly a century. But it seems that Hollywood’s days are numbered as other media capitals such as Bombay, Cairo and Hong Kong are set to dominate in this new era.